MARCH 2020

MARCH 2020

microtasking.ca

This resource is a print version of the content on the website.

Additional resources are available online.

Toronto Workforce InnovationGroup (TWIG) is Toronto’s workforce planning board and a member of Workforce Planning Ontario. TWIG's primary activity is to conduct dynamic labour market research and monitor workforce developments. TWIG also engages employment stakeholders with mandates that include Toronto. By working together, we identify workforce needs, gaps and opportunities and disseminate information.

TWIG Staff

Tinashe Mafukidze-Wingfield, Executive Director

Mahjabeen Mamoon, Lead Research Analyst

TWIG acknowledges the participation of many GTA workforce stakeholders

community groups | colleges and universities | educators and trainers |

employers | government | industry | labour | media | training institutes | special interest groups | standards bodies

Research Participants

Significant contributions were made by participants in the project's roundtables and workshops. They are acknowledged throughout.

Funded by

Ministry of Labour, Training and Skills Development

Senior Researcher

Cheryl May

Research Team

Marco Campana

Alastair Cheng

Maggie Greyson

Ana Matic

Goran Matic

Academic

Prof Michelle Buckley,

University of Toronto

Julian Posada,

PhD student

University of Toronto

UTSC Urban Political Geography students (fall 2019)

CC 2020

TWIG is part of Workforce Planning Ontario. The network of 26 planning boards is funded by the Ministry of Labour, Training and Skills Development. Each board is as individual as the community it serves. However, the network also works together to identify and plan for fast-growing sectors.

TWIG maintains a focus on the technology industry. In Toronto, new jobs are emerging through infotech and biotech advances. Full-time employment grew more slowly than the city average, adding 31,930 jobs (2.8%) from 2018 to 2019. Part-time employment added 14,980 jobs (4.0%). Trends point to a long-term increase in part-time employment in Toronto.

The number of people in standard full-time employment is also falling. So you might be familiar with gig-work and the sharing economy. Yet many people are unfamiliar with microwork. It is an outsourcing method that shifts jobs to many isolated tasks. A microworker takes on a variety of different HITs from many sources through an internet platform. Two of the leading microwork platforms are Figure Eight and Amazon Turk. They represent a marketplace where outsourcing clients post tasks for microworkers.

If you haven’t heard of microwork, try bringing it up in conversation. You are likely to find that you know someone – or someone who knows someone – who does.

The number of people estimated to be microtasking in Toronto is still small, so they may not be a microworker. But they may well post tasks on one of the platforms. Canada’s demand for microworkers is high and the workforce is global. In fact, according to the Online Labour Index (2016), Canada is in the top five countries for employers buying labour over the internet.

Indeed, corporations are breaking jobs into tasks to improve their bottom line. Yet, academics, political parties, the creative industry, and many others generate "human intelligence tasks" (aka HITS). The work includes complex surveys, digital recordings of experiences, and “predictions about political events.”

Verifiable statistics are not available for Toronto, so TWIG used foresight for this study. Experts, designers, policymakers, and gig workers contributed to all phases of the research. Together, we identified the changes that are taking place in Toronto’s workforce. Then we created four microwork futures and strategic perspectives to support planning.

The research topic went beyond microwork in Toronto. We offer this deep dive into microwork to anyone who is thinking about the future of work.

Cheryl May

Senior Researcher, Microtasking Project

March 2020

MICROWORK:

FROM JOBS TO TASKS

Why look into microwork in Toronto? by Cheryl May

Five questions about microwork by Marco Campana

Microwork's popularity among students by U of T Student

Microwork as a quick fix to ease the cash crunch by Valeria Gallo Montero

TWIG's microwork reading list by Cheryl May

Kristy Milland: The state of microwork by Marco Campana

Inclusive economic development by the City of Toronto

Digital platform worker initiatives by Statistics Canada

Amazon Canada is placing itself at the centre of Canada’s tech industry. In 2018, Amazon opened a 113,000 square foot Tech Hub in Scotia Plaza. In September 2019, Amazon announced a Scarborough fulfilment centre – its 12th in Canada. These initiatives represent 5,000 full-time jobs in Toronto, Scarborough, Brampton, Mississauga, Milton, Caledon and Ottawa.

Amazon offers many traditional and stable full-time jobs. Toronto’s Mayor, John Tory, expressed his support for the Tech Hub:

Microwork platforms are scalable tech ventures that earn mega-profits. The revenues of the top corporations are larger than the GDP of many countries. Amazon is one of the top four largest companies in the world by market value. The others in order of size are Apple, Microsoft, Amazon, and Alphabet (Google). Last year, Amazon’s net revenue was 232.9 billion USD, up from 177.9 billion USD in 2017.

There’s no doubt that microwork is a growing field, dominated by mega-corporations like Amazon and Google. The World Bank report, The Global Opportunity in Online Outsourcing, provides an in-depth look at the state of online outsourcing worldwide.

Understanding the technology industry and technology jobs is critical for workforce planning. New jobs are emerging through infotech and biotech advances. New forms of work are the result of globalization and socio-economic change.

What TWIG considered in this project is the work that is enabled by technology platforms, called microwork. The report features points of view on microwork, essays and foresight findings. Finally, we arrived at five strategic perspectives, which are ways to think about the future. They are the final output of the foresight method used for this project.

The OECD’s Employment Outlook 2019, considers the labour market and the future of work:

OECD’s infographic data based on data on Employment Outlook 2019.

Based on conversations with Toronto employment service providers, microwork is still a relatively unfamiliar form of work. Employment and other community-based agencies need to help job seekers navigate what appears to be an emerging labour market reality in Toronto. But it’s a challenge.

And not surprisingly, we are finding more questions than answers as a result of this project. However, awareness is growing about this almost hidden, but growing segment of the gig economy. Indeed, all the signals collected for this project suggest that we should be paying close attention.

The labour market is changing, and service providers have the ongoing job of balancing both employer and client needs. Conversations generally reflected two main areas of concern:

Employment service providers are curious to know more about microtasking platforms. They also want to know whether the employers they work with are using or will use microtasking in their supply chain. Here are the five main questions and a breakdown of the subset of questions related to each one.

It’s hard to know how big microwork is, or is going to be in the city.

So, how much should human service agencies with limited resources give their attention to microwork in Toronto?

Service providers want to know to prepare clients. If clients do want to explore microwork as their main income source or as a side gig:

Research analyst, Alastair Cheng, notes that the employers and industries currently using these platforms are primarily tech companies.

If microwork is on the rise, service providers need to understand what IT clients need to know. How do service providers prepare clients with IT experience?

So, it’s not just about microworkers. IT clients might also be doing the outsourcing for the company that employs them.

For reporting purposes, most agencies are focused on getting someone a full-time job. So that’s the measure of program success. Microwork disconnects workers from employers. They work on tasks, on a web portal (or app) and are never in contact with employers/requestors.

How do you document this type of work? What proof does a worker have that they did work for a company? Microtaskers work through the portal and cannot get references. But, employers are still looking for traditional references.

The Internet Institute’s members have produced relevant research such as Platform Sourcing: How Fortune 500 Firms Are Adopting Online Freelancing Platforms. Employment service agencies are well versed in the broader gig economy and are preparing clients for this shifting work reality. But the conversation about microwork or task-based work hasn’t come up.

Employment service agencies work with Toronto employers and connect them with talent. Is microwork an area where they want to build suppliers? Can agencies help source microwork talent? What’s the potential role here?

Microwork is not traditional full-time employment. How can service providers talk to employers about microwork? It would be helpful to work with them. If they’re looking for this type of worker, then agencies can prepare clients for that reality.

Employment service providers update curriculum and workshops to ensure clients have the most accurate picture of the Toronto labour market. They are also starting to provide training on the higher-skilled aspects of gig work. Should they incorporate microwork into their training program?

I found conversations, research, and other information on microtasking in the GTA through social media. The primary platforms I used were Reddit, Facebook, and Twitter. On these platforms, users discussed how microtasking allowed them to make extra money. The discussions on some of the threads also included what microtasking is, and the applications used to microtask.

I also spoke with friends and classmates to see if they had heard about microtasking, or did similar work to microtasking. When browsing the internet some of the microtasking jobs and small jobs I saw were on my YouTube feed. Some of these microtasking jobs showed up when streaming online shows and websites. One-off tasks usually don’t pay, however, they do guide you to more sources and links if you want to continue answering surveys or want to earn money.

As a group, we also concluded that microwork was more prominent in the United States than Canada. U.S companies are the primary source of microtasking jobs however, many jobs are open to anyone regardless of their location.

Some of the data found after doing research on microtasking:

Many students may want to microtask as a way of making extra pocket money or to support themselves while in school. As a student, when I was reading about microtasking I was able to relate to this. It does give you some money for doing small tasks that you can do on your own time and can access through a laptop. For stay-at-home parents, microtasking is a way to make some money when not busy with other responsibilities.

One clear advantage of microtasking is that each task takes a small amount of time and you can pick up tasks when you have time. This is very different from having a part- or full-time job. Microtaksing also gives you flexibility as it allows you to decide what tasks you want to participate in.

I found this interesting, as it gives users flexibility but also a choice. In conclusion, microtasking is a job that is accessible to almost everyone. It is a way to make extra money or have a side hustle. In our collective signals, we did see some people who did this as a full-time job but it was not common. Microtasking as a side gig was more common.

When scanning articles, I found it difficult to find information about microwork’s popularity more specifically in Toronto. I was able to see some opportunities listed on online news articles, blogs, and social media feeds. When speaking to my colleagues, I found they encountered the same issues. We found some sources for Toronto but started to realize that microtasking was not specifically in Toronto. Microtasking was more of a global gig/job. Another challenge was finding specific opportunities. Microtasking is not advertised as a single job. Instead, microworkers find work through an application that lists jobs. An example is Timebucks, which is a website that allows you to select surveys you want to answer.

Questions that came up were:

Microtasking is a form of precarious work because of the low pay rate. It was interesting to talk with other students who are combining a regular job with this type of work to make a living or extra money. It could show that extra income is wanted and needed by people to meet their expenses. This made me think deeper about the types of jobs people have and how much they are being paid. It also made me consider how the concept of precarious work differs from country to country. Finally, I question whether precarious work will become more common across all age groups in the future.

Overall, microtasking is a sharing economy trend and a quick fix to ease the cash crunch. The appealing aspects are:

In particular, I found microtasking targeted toward young adults. Therefore, the target group includes students, recent graduates, and individuals in need of extra income. The appeal of an additional “convenient” income stream is a draw. Moreover, microtasking had a lot of positive feedback from users. People dealing with the high cost of living in Toronto see it as a solution that meets their economic needs. So microtasking is a convenient way to earn extra income and it can be fit around a demanding student schedule or anyone’s busy daily life.

Given this, microtasking seems like a straightforward, quick fix to ease the cash crunch many Torontonians face. It is, however, a helping hand. It is not a permanent or a stable income to depend on.

Unfortunately, there is a lack of information about microtasking for people who are considering it or involved in it. There is very little information about:

Furthermore, there should be more public knowledge of the legal aspects of this type of work. People need clear information about the employment structure and rights. Also, protection, rights and responsibilities, and health and safety standards are missing from public policies for individuals who engage in microwork.

Something that I found to be interesting is a sense of encouragement to take part in the sharing economy overall. The sharing economy extends from peer-to-peer sharing to crowdsourcing, to microwork. Many people like the idea of helping each other out. In some ways, I felt it could be compared to the "good old days" when neighbours could ask each other for favours. This is a connection that I find interesting to think about.

Following the sprint, the research team identified 12 trends that surfaced in the signals. We reached out to experts in the fields of employment, labour market, workforce trends, and equity to develop the drivers behind the trends and hosted two virtual roundtables. The experts also identified the need for a short reading list.

Together with my fellow researchers, Marco Campana and Alastair Cheng, we reviewed over 150+ articles, reports, research papers, and other media. Together with the signals data provided by students, this represents a harvest of over 500 signals. The following 12 resources will help anyone interested in microwork get up to speed quickly. TWIG's full microwork library, representing the top 100 resources, is available at microtasking.ca.

Digital automation encompasses the various technologies like machine learning, often considered in the context of AI. In this study, we are using 9% to 46% as estimates for the Canadian workforce susceptibility to automation. The statistics come from recent reports by the OECD (9%) and Brookfield Institute (46%).

The literature on this topic varies. Because our focus is foresight, we have set aside the question of how much job loss automation will produce. The related trend depicts the ongoing incorporation of “AI” into both business and other aspects of life. Accordingly, growth in AI drives growth in microwork. Anthropologist Mary L. Gray and computational social scientist Siddharth Suri emphasize this point in Ghost Work, a seminal book that belongs in your microwork reading list. If you like to listen, the Ghost Work podcast episode with Gray also merits attention.

Research-based on automation data flags job transitions out of automated roles, and a diminished share of value-added for labour. Autor and Salomon’s Is automation labour-displacing? conveys results based on OECD data since 1970. Added to this, a recent study by economists James Bessen, Maarten Goos, Anna Salomons, and Wiljan Van den Berge, posits that automation is a slow process, making it difficult to prompt a public response.

The Bank of Canada study, The Size and Characteristics of Informal (“Gig”) Work in Canada, added additional questions to the consumer expectation survey as a way to gauge participation rates. One-third of respondents report participating in gig work. In the context of precarious work, gig work is most typical among people who are historically affected by unemployment rates. In other words, young people, part-time workers, and specific regions.

The Oxford Internet Institute’s Online Labour Index (OLI) tracks supply and demand flows. It does this by tracking projects and tasks across platforms. Canadian demand and supply stats can be viewed using the primary visualization tool and worker supplement on the linked page. The platforms monitored by the OLI encompass everything from web development to microtasks. So, the researchers view this data as indicative of the dynamics in the broader platform freelancing market. Still, the employers and industries that are currently using these platforms are primarily tech companies.

OLI-related publications provide details about the online freelance labour across countries and occupations. Likewise, the Internet Institute’s members produce other research. As an example, Platform Sourcing: How Fortune 500 Firms Are Adopting Online Freelancing Platforms, provides helpful context.

Scoping out “microtasking” has been an ongoing challenge. One of the reports that shaped the scope of this work is the ILO’s Digital Labour Platforms and the Future of Work. (p. 16-22). The report draws on a clear picture of crowdsourced work based on a 2017 survey of crowdworkers.

Despite the ILO’s incredible work, getting apples-to-apples data about worker demographics is challenging. The World Bank produced The Global Opportunity in Online Outsourcing, a 2015 global assessment of outsourcing as a driver of growth in developing countries.

Your microwork reading list will also benefit from the following three current recommended resources. They cover the broader context of microtasking as a global phenomenon.

Kristy: The state of microwork is invisible. I know Statistics Canada is trying to figure out how to measure it. How do we measure it just in the Canadian labour market? How many people are doing this? Who is doing this? And so the problem right now, I think, in assessing the market here is that no one knows.

In my experience, which is with the Amazon Mechanical Turk’s community, I was the only one in Toronto. There were others in Ontario, there were others throughout Canada. But as far as I knew, on Mechanical Turk, I was the only Torontonian that was part of the community.

Now, that leaves out between 40,000 and 90,000 people. One of them could be from Toronto, but it seems to be pretty low scale, as far as something that is kind of the stereotypical platform like Mechanical Turk. When discussing the state of microwork, there are a lot of platforms that we don’t know about. And the reason is the platform is only here for the work and then gone once it’s done.

So who is doing that kind of microwork? Probably a larger percentage of people. Especially if you start looking to people who might be doing it as immigrants or students. People who are looking for jobs and maybe are typically or traditionally excluded from the labour market. And they are the people that are the hardest to reach. The hardest to find and count.

On Mechanical Turk, there’s a decent percentage of people who are doing microwork on a beer money basis. So they’re here and there, up to a full-time basis. I think there are way more at the bottom end of that. But there are definitely people out there doing it. And I think the major problem is how do you even ask them if they do this work?

Kristy: Yeah, beer money is going to be the largest amount of people. And these are the people who are going to identify as a microworker and are the least likely to think about it as being work.

So, again, it’s hard to find them and reach them as a result. But I would say, people who dabble in it, even for a short amount of time and give up on it. They’re going to be the greatest number of workers at any given time.

When you look at that, it’s also about the definition of microwork. For example, surveys on sites like SurveyMonkey. These sites pay you in gift cards and things like that. That’s still microwork.

And when you start including that, the numbers are going to go up dramatically. Especially if you look at specifically surveys or contests, which I personally also view as microwork. Because they entail a lot of work on social media. Maybe you run a website, things like that. So if you start to broaden the definition of microwork, and include people tiny tasks for money, you’ll include a larger number of people.

Kristy: As a law student, legally we are woefully unprepared. And that is not just labour legislation. It’s also tax, health, and safety legislation. We need to sit down with the laws we have in place and question are these going to be adequate. Because it goes beyond microwork. It goes to all independent contractors. Microwork is a small section of this bigger problem.

You mentioned social services, individuals who do microwork. They’re paid so little. Obviously they don’t do microwork because they could do something else, right? So these are people in desperate situations. They’re the ones who are more likely to access the welfare state. And as a result, they’re going to be a larger drain on government funding, but they make so little they don’t pay back into it.

And also their employers don’t pay into it, right? They have no ability to give back. They’re not built for giving back. So the problem becomes who’s going to pay for this and protect these workers.

I am permanently disabled because of my work. Who pays for that? I didn’t have workers comp, but live in Ontario and have health coverage. But who pays for that health coverage? I was paying income taxes, and I was paying a lot of income taxes, but for workers who might have been making less than I was, who’s paying to make these services available to me? And if we’re not helping workers who are hurt, then we’re losing workers and suddenly our unemployment goes up. And these are people in now on welfare and ODSP. This is a spiralling problem.

There are so many great suggestions on this from academia, but addressing it is about labour legislation. Who is responsible for these people and for paying into the state to give them benefits? Who takes care of these people when they’re hurt, sick, or unemployed? And then looking beyond that, how do these people pay their taxes? And how did the companies that employ them pay taxes if they’re not necessarily in Canada? 10 years is a very good timeline to start thinking about this. Because if we don’t start looking at this quickly, the government is going to be in dire straits financially. Both in supporting these people and in the fact that just the money won’t be coming in.

Kristy: Absolutely. And the Conservative government already thinks we’re a mess. I can only imagine how bad it’s going to get when over 50% of workers are independent contractors, and thus not privy to all of these legislations.

Kristy: I am definitely an outlier, who came from a middle-class family, went to exceptional schools, and was in a gifted program. Having a leg up and I think that set me apart in the microwork economy as well. I came into it using a computer since I was born, which a lot of people my age didn’t.

So I was programming, creating websites, building communities, and considered a super Turker.

There’s a group of us, less than 1% of the workforce. We come in with some sort of privilege, whether it be programming or confidence. There are so many things that make you a better microworker, but even I hit the ceiling.

I do not see that gig work necessarily gave me any opportunities. I made opportunities for myself. And I’m the one that was able to do that to leverage.

For example, the media helped get out there and then that helped me get into law school. But there’s some interesting work coming out of the US. It started with SamaSource attempting to use gig work to improve the skills of people in rural areas who couldn’t get work. It gave them an opportunity that they would never be able to find otherwise.

There’s Saiph Savage at UNAM in Mexico. She started to look at how we can use gig work to help people with their English, reading, or writing.

There are opportunities for that. But if we want to improve the state of microwork, it needs to be operationalized. You can’t just do that by going to Mechanical Turk. There are people who might say: “I’m focusing on writing this week. Because I want to get better at it. You’re going to get rejections if you’re not already good at it.”

You already have to have the skills in order to be able to leverage the work that uses those skills. It’ll be interesting to see how Saiph works with that.

But otherwise, how do you put AMT on a resume? And I have, I did, but I’ve removed it. Because explaining what I had done all those years wasn’t a benefit. Instead, I pretend I’m 27 and have only worked for a minute. It led to more questions than anything. What is Amazon Mechanical Turk? And now I’ve spent a 15-minute interview explaining that. They’re all horrified, but they don’t know anything about me.

So, yeah, it doesn’t lead to bigger things. It’s not like starting in an Amazon warehouse and working your way up. James Blair, who works at Amazon is now head of AWS or something. He started on the warehouse floor. I would love to see a Mechanical Turk worker get hired at Amazon.

And we have programmers. 70% of the workers in the US have a college education. Over 80%, I think it might even be 85% of Indian workers have a degree. These are not people that shouldn’t be able to work somewhere else, do something better, and move up in the hierarchy. But they don’t. The only platform I’ve seen that happen on is Lead Genius. They allow you to work your way up to project manager and stuff like that. But even that has a ceiling. I don’t see people that have worked there in executive positions. I’m looking at something like Lead Genius, and thinking- how can we use this kind of work? There’s an interior design platform in Italy, I think it’s called 99 designs. When a student goes to an interior design college, they sign up there and build their portfolio.

And then once they have a portfolio, they can go into the real world. It’s horrible but mandatory. Because it gives them an opportunity.

Kristy: When I think about this, I kind of think about things like UBI [Universal Basic Income]. And I’m not a huge proponent of UBI. Because I think the money goes back to the same rich people. But this would be a situation where universal basic services come into play. Like free internet and free computer equipment upgrades with a fast connection, for example. Then, your wages would go further. Maybe that’s tied to something like social services? Training is hard. Definitely, English language training would be important for immigrants, and individuals who do not have a great education and want to do higher paid tasks. Like the move from Mechanical Turk to Upwork.

And then, I think, research as to what the high paying tasks are on sites like Upwork or similar, more niche sites will provide courses to individuals who want to do more than just labelling an image black and white or colour. Especially for younger workers.

Ontario has a powerful sector in the cooperative sector. So I would love to see government funding for cooperative gig work and microworking. Because if we can do that, we can support workers who are creating their own platforms. We can also offer training in marketing, social media, website design, etc and get them to own their own platform.

Now you have Canadian companies, paying Canadian taxes, employing Canadians to do this work. In many ways, they can be more competitive, offer greater quality services, and draw in customers. And that’s super easy to do. There are people now who are affiliated with The New School.

They are looking at this in the Cooperative Platformation movement. Google is paying them a million dollars to create modules. Because they want people to build cooperatives.

I think Canada could lead this sector because our cooperatives are well supported. Legislatively, there’s a really well-built infrastructure. If we could get workers into those roles, and leaders are willing to do this, we’d solve a lot of problems right off the bat. And then you’d have a community of workers, willing to answer questions about the state of microwork.

Right now, we’re relying these workers are relying on unaccountable companies in other countries. We don’t know who they are. The biggest issue with the state of microwork is the people who use the platform. Like customers of the platform and businesses, for example. Because they’re in the same boat. If we provide accountable, Canadian solutions to both of these groups, we’ll benefit everybody involved. I think it would really move the industry up in stature and make it better all around. It’s also something that we might be able to respect a little more than (we do) right now.

Kristy: Yeah, absolutely. I think Amazon Mechanical Turk, for example, I liken it to Paypal. It’s a platform. PayPal and Amazon Mechanical Turk don’t instinctively say: ” we’re going to have bad actors and bad pay! It’s going to be terrible!”

There are some things that are built into the system which can lean one way or the other. That’s problematic, but it’s just a platform and microwork is a form of work. And it’s about how you use it and how you build the platform, and how you access it as a customer (a business). That’s what makes the state of microwork bad or good.

So whether it’s positive or not depends on the actors involved. That of course, is tripartite: employers, employees, and then the government. The state of microwork is up to them.

Kristy: I think it definitely depends on I would say the class system and microwork. So, if they are low paid microworkers, they’re associated with where they work. For example, a lot of the low paid workers will be on Crowdflower or Amazon Mechanical Turk. And so they will refer to themselves as Turkers, or as Crowdflower Workers.

If they are higher paid, they will work on multiple sites, and see themselves as entrepreneurs, independent contractors, or consultants. It depends a lot on how much they’re making, how they’re working, and how much they’re working. But people who do this for beer money are hobbyists. They won’t think about it at all. If you ask them what their job this will tell you their main job. You say: “what about this?” They’ll say: “It’s just something I do at night while watching TV”. They will have zero identity.

It’s kind of multifaceted how they see themselves. I’ve never heard anyone call themselves a microworker. Crowd Worker maybe. I think that would probably be the most common term I’ve heard from workers themselves. Otherwise, it’s always: “I’m a Turker” or: “I do work on Upwork”. But again, the higher the pay, the more likely they are to say: “entrepreneur”. Those American Dream type terms.

Myself when I put it on my resume, I put microwork consultant or microtasking. Micro Tasker is one I’ve heard before, but again, I think it’s pretty rare. It’s mostly Crowd Worker.

Kristy: Identifying them is going to be difficult. I know Statistics Canada is doing focus groups right now. I would highly recommend getting in touch with them and seeing what kind of data they’re producing. That might help. I had a chat with them about the state of microwork. Because they’re really struggling with the state of microwork. But they might help you find these people, figure out what terms they are using, and what sources there are to get access to them. That is probably your best bet.

When discussing the state of microwork, It’s really tough to nail down workers, but they’re going to be the ones that you most need. There’s not a lot being done in this, which is a shame.

Kristy Milland is currently working towards her Juris Doctor degree at the University of Toronto. Previously, she was community manager of Turker Nation, the oldest community for Amazon Mechanical Turk (AMT) crowd workers. In this role, Kristy had her finger on the pulse of the Turker population, with a deep understanding not only of how to get the best work quality on the platform but the labour issues that surrounded microtask crowd work. As a gig worker on AMT, Kristy experienced the precarity of this form of work first-hand. She took it upon herself to get as much attention to the issue as possible so that nonprofits, unions, academics, government, and industry might take up the cause and determine how to make crowdwork a job people could be proud to have.

She has spoken around the world about the ethics and exploitation of crowd work, how to use Amazon Mechanical Turk effectively while still respecting the workers, and the importance of regulation of crowd work as more and more jobs are being taken away from skilled, educated workers and given to the crowd. She has stepped back from her activist role to focus on law school. Her research interests involved whether the current legislative schemes of Canada and the U.S. concerning labour and employment were of use to gig economy workers, and, if not, how they could be changed to ensure that all gig workers could be protected from exploitation.

website: kristymilland .com twitter: @TurkerNational

TWIG is a key participant in the future of work conversation, and the exploration of microwork in the labour market interests the City of Toronto.

Over the past few years, inclusive economic development was an emerging theme across a number of City of Toronto divisions. To be prosperous and sustainable in a globalized economy, the City of Toronto must succeed on a number of fronts. Examples include affordable housing, accessible public transit and full-time, well-paying jobs.

The Economic Development & Culture Divisional Strategy 2018-2022 establishes goals, which support Toronto’s business and culture sectors. It also ensures that all Torontonians can benefit from a vibrant economy. The two most important goals of the strategy are “Inclusion and Equity” and “Talent and Innovation”. Both goals support the creation of good jobs in Toronto.

Addressing many of the challenges facing Toronto – such as gun violence, a shrinking middle class, regional transit, and precarious employment – will require us to work collaboratively.

In a recent meeting, over 150 GTA-based policy development professionals created policies which align with the new Corporate Strategic Plan.

Equity and inclusion principles cut across all our programs and services, including economic development. One example of such a program is the Indigenous Centre for Innovation and Entrepreneurship (ICIE), a federal government-funded program.

The future of work will look different than it does today. The City of Toronto is collaborating with our partners – including TWIG. This will ensure that jobs in the future are sustainable and all residents have the opportunity to benefit from Toronto’s economic success.

In 2017, Statistics Canada released survey-based employment estimates on the ‘gig’ economy including the number of providers of peer-to-peer ride-hailing services in Canada. More recently, Statistics Canada published historical estimates on the number of gig workers based on tax information. On behalf of Employment and Social Development Canada, Statistics Canada is currently conducting a qualitative study to learn more about online platform employment, particularly about the profile, motivation and working conditions of digital platform workers in Canada. This particular research focuses exclusively on online platform workers whose jobs, projects or tasks are delivered online.

Statistics Canada was pleased to find out that the Toronto Workforce Innovation Group is contributing to the analysis of microtask work and look forward to continuing a dialogue to promote the release of statistical information on this segment of the working population for various jurisdictions.

Statistics Canada, The sharing economy in Canada (2017)

In an attempt to measure the impact of the sharing economy, Statistics Canada asked people living in Canada the extent to which they used or offered peer-to-peer ride services and private accommodation services.

Statistics Canada. 2017. The sharing economy in Canada. The Daily. February 28. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 11-001-XIE.

Statistics Canada, Measuring the gig economy in Canada using administrative data (2019)

Using data from the Canadian Employer-Employee Dynamic Database and the 2016 Census of Population, a new study found that the share of gig workers among all Canadian workers aged 15 and older increased from almost 1 million workers (5.5%) in 2005 to about 1.7 million workers (8.2%) in 2016.

Jeon, S.-H., H. Liu, Y. Ostrovsky. 2019. Measuring the gig economy in Canada using administrative data. Analytical Studies Branch Research Paper Series, no. 437. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 11F0019M. Ottawa: Statistics Canada.

Platform Workers in Europe: Evidence from the COLLEEM Survey (2018) >

Estimates indicate that on average 10% of the adult population has used online platforms for the provision of some type of labour services. However, less than 8% do this kind of work with some frequency, and less than 6% spend a significant amount of time on it (at least 10 hours per week) or earn a significant amount of income (at least 25% of the total).

US survey from the Bureau of Labour Statistics on platform work >

May 2017 estimates of electronically mediated workers as decoded by the BLS. The estimates include all people who did electronically mediated work, whether for their main job, a second job, or additional work for pay.

MICROWORK INSIGHTS:

FROM PRESENT TO FUTURE

Chapter 1

Microwork: An introduction by Julian Posada

Chapter 2

Microworking in Toronto by Marco Campana

Chapter 3

Invisible Gigs: Microwork in Canada by Alastair Cheng

Chapter 4

Aggregate action, complexity, and microwork by Ana Matic

Chapter 5

Microwork futures: Strategic perspectives by Cheryl May

Chapter 6

Investigating personal futures by Maggie Greyson

With our current resources, we can create, sustain, and regulate intelligent machines. From the extraction of resources to the treatment of information, the creation and distribution of technology to the disposal and recycling of outdated devices, artificial intelligence requires workers at every step.

In this context, microwork involves workers that provide and transform data destined to train and improve machines. These independent contractors work remotely and perform fragmented tasks – often requiring just a click-through online digital platforms. Their actions are essential for automated and intelligent systems since they play a part in the learning and correction of these systems, sometimes even impersonating these systems when they fail to provide results.

One of the first and best-known microwork platforms, Amazon Mechanical Turk, was named after an 18th-century automaton that toured throughout Europe, playing with—and even defeating—individuals at chess. In reality, and unknown to spectators, a concealed human player operated the automaton from within. Thus, much like the Mechanical Turk, microwork platforms create the illusion of automation by outsourcing the labour of their workers and rendering their actions hidden to the public. This “invisibilization” is part of an ongoing historical trend that includes 19th-century pieceworkers who effectuated small tasks from their homes for factories, or human computers that provided calculations for research institutions.

Every second, web users upload an incredible amount of digital content to platforms, including video, audio, and images. Many companies deploy algorithms to detect and remove inappropriate content posted online. However, automated systems are oftentimes incapable of identifying it. If required, humans need to step in, review these posts, and remove them. These workers often suffer from intense psychological distress due to the nature of the content they are evaluating which, in some cases, includes examples of extreme violence and exploitation. Big technology companies outsource this labour to other companies, but these workers also operate through microwork platforms. As independent contractors, these workers are not entitled to psychological help through their employers. In some cases, confidentiality contracts forbid workers from discussing the nature of their work.

Since microwork often involves externalized workers who can operate from anywhere in the world with an internet connection, companies rely on digital platforms to coordinate the offer and demand of work. In general, platforms are programmable digital infrastructures that exchange data between different users. They include social media websites like Facebook or e-commerce companies like Amazon.

Some of these platforms specialize in labour exchanges, including freelancing sites like UpWork and on-demand apps like Uber. From a labour transaction and geographical scope point of view, not every platform is the same. Some platforms allow complex activities, while others outsource fragmented tasks; workers may perform tasks bound to specific geographic locations, while others can work online. In an ecosystem of platform labour, microwork platforms are web and crowd-based. Requesters allocate the same tasks to a multitude of users around the world.

The French DipLab project identified the following tasks available on microwork platforms:

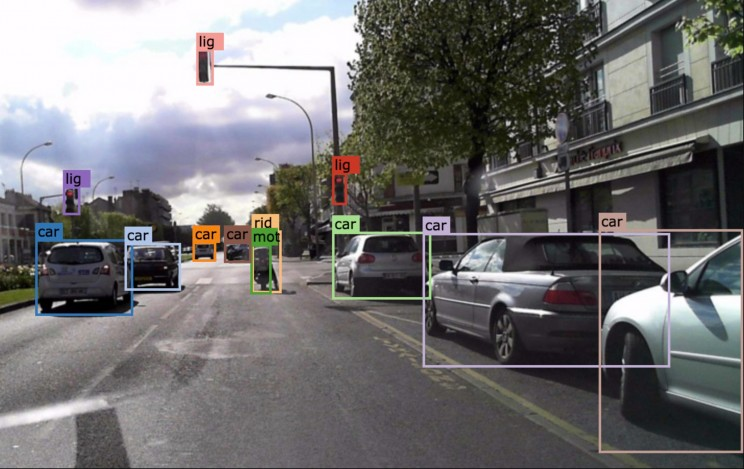

Data entry • Image labelling • Document digitization • Survey responses • Content moderation • Software test • Product classification • Web searches • Voice recording • Translation • Transcription

Microwork platform workers are a hidden population due to the nature of their jobs, which makes them difficult to reach. Research on online work, including micro-tasking but also other types of remote freelancing, suggests that the supply and demand for labour is often—but not always—distributed between high-income countries and nations in development. The demographics and geographies of micro-work change depending on the platform. For instance, workers of AMT are primarily male and located in the United States and India. At the same time, those working for French platforms are predominantly women and located in France and francophone areas of Africa.

In most cases, the people who operate these platforms are not considered employees or workers, but independent contractors. Therefore, they lack the social protections often tied with employment such as fair and guaranteed income. Nonetheless, workers value the flexibility of platforms which allows them to work remotely from anywhere in the world, and the revenues from these platforms are, in many cases, essential, even as secondary sources of income.

Online platform work is also characterized by superfluity and fungibility. In other words, workers feel that they are easily replaceable due to the large number of workers in relation to the offer of tasks, and platforms rely heavily on reputation scores and evaluations to distribute these tasks. Workers are constantly reminded that they can be fired quickly and at any time, as platforms can delete their accounts easily and without recourse. The intermediation of platforms further alienates workers, as some ignore the identity of their employers are, and the majority don’t know the function of their work.

In recent years, there has been an emergence of new microwork platforms that shift away from the business model of earlier platforms like AMT, which allowed different kinds of tasks. These platforms specialize in a particular sector, such as exclusive training for artificial intelligence systems. Moreover, while non-specialist platforms coordinate the advertisement of jobs and the recruitment of workers, these newer platforms outsource these elements, making their operations challenging to trace. Some scholars classify this type of platform as “deep labour.” Take, for example, platforms that focus on training algorithms for self-driving cars that request their workers to provide image classification, object detection or tagging, landmark detection, or semantic detection. Daily internet users provide similar data when they are asked to detect objects through ReCAPTCHA to prove that they are not robots. However, self-driving cars require more complex tasks fulfilled by microwork.

Tagging for self-driving cars

Segmentation for self-driving cars

Due to geographical dispersion and lack of face-to-face communication between workers, achieving collective organization—and unionization—in online labour contexts remains difficult. In the case of microwork, workers mainly rely on online communication. For instance, 90% of workers on AMT use forums to communicate. In the past, workers have successfully pushed for better working conditions, even on their own. One of the best examples of worker and academic action towards fair online labour is Turkopticon, which allows AMT workers to rate their requesters. Before its creation, workers were the only ones being evaluated by their employers, creating a significant imbalance of power. Thanks to this initiative, workers can rate requesters in terms of communicability, generosity, promptness, and fairness.

Regarding regulation, it is challenging for governments to address microwork platforms due to the transnational nature of their operations and the difficulty of assessing their transactions. In some cases, governments and policymakers, notably in developing countries, welcome online labour platforms as a means of reducing unemployment. So far, regulatory examples of labour platforms include mostly location-based ones like Uber instead of web-based cases.

If you’re not familiar with the term “microwork” you’re not alone. But you’re likely familiar with the notion of the gig economy. Think of microwork as the hidden, service-based, and most precarious work of the gig economy. Here are some of the names you may have heard:

Before designing solutions, we needed a common definition. The definition used for this project is:

Microworking in Toronto exists on the fringes of non-standard employment. At the same time that it is falling outside the scope of many workforce stakeholders, demand is growing. Microwork also spans a vast number of occupations – from knowledge workers to service-level workers. Microwork’s near-invisible status is problematic.

One of the troubling trends we identified is People as a service. The demand for task-level outsourcing is increasing. And as microwork platforms simplify coordination with a vast pool of taskers, permanent jobs can be broken into specific (including very specific) tasks. Microwork.

Studies show that the number of people in standard full-time employment in Toronto is falling. The Toronto Foundation’s Vital Signs Report Issue Area 3: Work found that “Young people and newcomers are disproportionately finding themselves in these jobs.”

Note: The CCPA study focused on Uber, food delivery, cleaning, home repairs and others.

The Brookfield Institute report, Future-proof: Preparing young Canadians for the future of work, considers whether part-time microwork and other gig economy work create a career pathway, or only reinforces existing precarity. Even more thorny is the question of who might experience which path.

Drawing on over 500 signals, we also identified the T.O. grind as a microworking in Toronto trend. Although the world’s biggest microwork platform, Amazon Mechanical Turk (AMT), has been around since 2005, microworking in Toronto remains relatively unstudied. Added to that, the average person doesn’t know much about it. But there’s little argument that Toronto residents face rising affordability challenges.

The Online Labour Index confirms that technology is also creating much of the demand for microwork. We need to pay attention to Toronto’s rising global tech status.

The Bank of Canada recently released The Size and Characteristics of Informal (Gig) Work in Canada with new survey questions.

The Oxford Internet Institute’s Online Labour Index (OLI) regularly updates a comparison of supply and demand flows for online outsourcing platforms. However, the OLI represents the broader platform freelancing market, not just microtasking portals. Canada ranks high for employers using online outsourcing platforms. Hence, it is a growth area to keep an eye on.

Thanks to OLI, we know something about how many companies in countries are using online outsourcing platforms. We also know that it is increasing. On the other hand, little is known about microworkers themselves.

The TWIG microtasking project was designed to be open to microwork as high-skilled or low-skilled work. For the most part, however, microworking in Toronto means low wages, and it presently lacks benefits and job security.

The International Labour Organization (ILO) found that taking unpaid work into account, microworkers earn a median hourly wage around USD 2.00 per hour. The mean wages of microworkers amounted to USD 3.13 per hour.

So, not high-paying. Indeed, not even close to minimum wage in Toronto.

Recommended: What have we learned from the market for Online Labour? OLI

That’s how Vancouver microworker Harry K. describes searching medical images for breast cancer cells, then manually tagging them. As he explains to a Wired writer, it’s “tedious and detailed.”

The task’s especially slow for a nonspecialist like Harry: he works full-time at a large packaging company. “A couple of training screens” and a quiz were the only preparation required.

Harry found this work on what’s now called Figure Eight. Like Amazon Mechanical Turk, the platform helps easily outsource low-skill digital tasks.

The image-tagging “requester” here was a Harvard medical professor who co-founded PathAI. (The cancer diagnosis startup has since raised over $90m in funding.) Crowdworkers like Harry then competed to snatch up the tasks, as they would any appealing work on the platform.

Microwork quietly keeps the digital economy going. It’s vital for everything from training AI to bridging “automation’s last mile,” as when Uber uses humans to confirm driver identity. But many people don’t even know the workers handling such tasks exist.

This trend seems particularly significant for Canada. Employers here are hiring ever-more freelance digital workers, according to the Online Labour Index. It measures postings on five major freelance platforms to track broader trends. From 2016 to 2018, the indicator showed a 30% increase in global demand for online labour.

In this same period, though, postings from Canadian requesters actually doubled. And the sort of research fuelling Toronto’s AI boom has long relied on microwork.

It can nevertheless be difficult to evaluate the possibility of Canadians increasingly hiring or working through microwork platforms. Even Harry’s situation can quickly start to feel ambiguous.

His pay for the cancer image processing was incredibly low. A pathologist in the requester’s home country might make $80 USD per hour for such tagging. But Harry earned a cent per minute. Even outside Vancouver, the hourly equivalent doesn’t come close to covering cost of living anywhere in Canada.

But Harry also explains he quickly abandoned the cell-tagging task for other work. So we can’t tell how much it represents his broader microwork experience — or what the realistic alternatives might be.

He clearly got enough out of it previously to continue. Harry actually estimates he’s completed 25,000 other tasks. The earnings flexibly supplement his wages, helping pay legal bills and child-support from a bad divorce years earlier.

“If I had the opportunity to not do my day job and do crowdworking instead,” he ultimately says, “I would.”

Such tensions can make microwork difficult to interpret. Is it a creative hustle that can “provide a steady income,” or “a new kind of poorly paid hell”? Or something else entirely?

To properly evaluate any answer, we first need some basic facts about microworkers. How many are there, for example? What are they paid? And who are they?

Microwork markets are complex: highly varied, rapidly evolving and often opaque. So without such baseline information, discussion collapses easily into people talking past one another.

That’s partly because it’s easy to find support in such markets for a wide range of sweeping judgements about them.

This isn’t just a matter of individual anecdotes like Harry’s. As discussed later, whole microworker subgroups and task types can have very different features. So it’s easy to stumble by accurately describing one facet of the market, then simply assuming others are similar.

We wouldn’t make sweeping generalizations about 1980s “telephone workers” based on just the experiences of administrative assistants, hotline psychics or commodities traders. But similar mistakes regarding today’s microworkers can be tempting.

So we began this Toronto Workforce Innovation Group project by gathering all the available relevant research.

We soon realized there simply aren’t any studies on microwork in the GTA. This broadened our focus to the national level. And still, the basic fact is this: no one knows much. New research is bringing key points into clearer focus, though.

So this post reviews what combining all available sources can tell us about Canadian microwork. Along the way, it also highlights some key research findings (and challenges) about these new markets more generally.

There’s almost no direct, large-scale research about microwork in this country. This makes our most promising option the Canadian Survey of Consumer Expectations.

This Bank of Canada (BoC) questionnaire goes out quarterly to the heads of 2,000 households, selected to represent adults 18 and older in this country. For 2018, the surveys also included an informal work supplement. Like recent U.S. efforts, these extra questions focused on “gigs” or “side jobs” that otherwise don’t register in traditional employment statistics.

The supplement covered pay for offline services, from house-painting to eldercare. But it also asked about online earnings. Options here included driving for services like Uber, creating content (e.g. YouTube videos), and “getting paid to complete tasks online through websites such as Amazon Mechanical Turk, Fiverr or similar sites.”

This question makes the survey one of very few sources that specifically investigates Canadian microwork. And on average, 4% of respondents said they’d completed tasks online for money.

If nationally representative, the Canadian Survey of Consumer Expectations responses suggest just over 1,195,000 people earned microwork income in 2018.

More details would obviously be necessary to make proper sense of that basic number. But complications set in even earlier.

People often don’t understand themselves in the language of labour analysts. Pew found that by the end of 2015, e.g., 89% of U.S. adults still weren’t familiar with the term “gig economy.” And the intersection of informal and digital work is complex enough to trip up even specialists.

All this can make interpreting survey results challenging.

The U.S. Bureau of Labour Statistics sought information similar to the BoC survey with their 2017 Contingent Worker Supplement, for instance. But many respondents clearly misunderstood questions about digital platforms and “electronically mediated” work. Ultimately, Bureau employees had to manually check and recode responses.

The definition of microwork is also notoriously blurry, making this problem worse.

One basic challenge is that many different kinds of tasks can qualify. That’s why the recent International Labour Organization (ILO) report on microwork uses a 10-category classification. But looser, less standardized classifications remain common.

A 2019 Boston Consulting Group survey on the gig economy shows the research challenges this can cause. Their report doesn’t distinguish microwork from other “low-skill” platform-based services, such as house cleaning. So it ultimately can’t tell us much about either type of work.

Such blurring is also a risk for the BoC’s microwork question.

Among informal income options, it lists “completing tasks online” separately from “responding to surveys.” And BoC staff excluded the latter from their analysis of informal work.

But the ILO report just mentioned notes that 65% of microworkers earn income by taking surveys. This makes it the most common sort of work by a full 19% on platforms such as Amazon Mechanical Turk — also known as “AMT.”

So what might including online survey-taking do to this estimate of Canadian microworkers? Based on the BoC publication, it’s quite hard to know.

(Partly, that’s because the question actually combines completing surveys on- and offline. So even full access to the response data wouldn’t easily resolve things.)

But let’s say 0.05% of respondents picked the survey-specific option to represent their digital work, while not selecting “completed tasks online.” On average, this would take just one person per questionnaire they sent.

We might then increase our estimated population of Canadian microworkers by the same 0.05%. This would translate nationally into nearly 15,000 people — higher than the total 2016 census population of Fort Eerie, Ontario.

Such attempts to glean microwork insights from broader surveys also raise a more basic issue.

Even with many respondents, it can be hard to know they truly represent Canadians as a whole. For instance, the BoC survey’s online-only format might well leave platform workers over-represented.

On average, respondents each survey included in this analysis would have averaged 80 Canadian microworkers. But that number’s far too small to support generalizations about the microworkforce of nearly 1.2 million the BoC survey answers imply. We certainly can’t know anything about the socio-demographic details that matter most for TWIG’s project.

The challenge of representativeness is even clearer in our only other direct source for national numbers on microwork: Statistics Canada’s latest Canadian Internet Use Survey (CIUS).

The 2018 CIUS draws on responses from just over 14,400 people, secured by mail and phone. The survey had also just been updated for currency and clarity.

It directly asked participants if they’d earned money in the last year from “crowd-based microwork (e.g., Amazon Mechanical Turk, Cloudflower [sic]).” The survey also clearly distinguished this option from earnings through “online freelancing (e.g., Upwork, Freelancer, Catalant, Proz, Fiverr).”

Despite including the question, Statistics Canada didn’t release any data on microwork with the main CIUS results. And when asked, they explained the responses received didn’t allow enough certainty for publication. Any conclusions would simply be too unreliable.

More recent publications suggest Statistics Canada may ultimately be able to provide far richer insights. (See the last sections of this post for more on that.) But right now, we simply have no reliable information about how many microworkers there are in Canada — let alone Toronto.

Even without knowing their exact number, we hoped estimating Canadian microworkers’ earnings from international sources might still be possible. But this also quickly gets murky.

It’s occasionally simpler to treat using some platform as synonymous with doing a specific sort of task. But some platforms offering microwork also let people take on larger, higher-skill “macrowork” projects. And this opens up room for error.

The BoC’s informal work survey reflects the challenges here. As examples of sites respondents might use to “complete tasks online,” it offers both AMT and Fiverr. But the second is a far more general freelance marketplace. Work on offer there ranges from place-based street postering to mobile app development.

Workers on AMT might earn a cent per basic image-recognition task. But Fiverr’s highest-paid projects include complex video production, for up to $18,000 USD.

For those interested specifically in microwork, things then get even more ambiguous.

The survey’s definition of “tasks online” goes far beyond simple work like rating pictures. Examples provided include reviewing resumés, editing documents and doing graphic design. The questionnaire then gives both freelance computer programming and graphic/web design as entirely separate income options. Respondents could also select multiple options.

This isn’t just academic quibbling. It’s unclear how Canadian microworkers would interpret these options, and the result could be significant miscounting. Then this likewise undermines hope for any further insight from the survey responses, on topics such as average microworker payment.

Such concerns make the 2018 International Labour Organization report mentioned earlier invaluable. Digital labour platforms and the future of work focuses specifically on microworkers. So it paints a much richer picture of how and why people around the world use these platforms.

The study draws on several rounds of surveys and interviews. Researchers collected data from an international group of 2350 microworkers, reached through five leading platforms. These included AMT, CrowdFlower and Prolific. (This last specializes in recruiting participants for higher-paying research surveys and experiments.) The authors then used this data to study more general features of platform microwork and microworkers.

Throughout, they focus on exactly the sort of compensation and demographic details relevant to TWIG’s work.

Even factoring in the exchange rate, this obviously falls well below Ontario’s minimum wage.

The report unfortunately doesn’t provide any Canada-specific analysis. Respondents nevertheless included Canadian microworkers. And their earnings presumably inform the authors’ broader conclusion that North Americans using these platforms make an average of $4.70 USD per hour.

But as with the BoC results earlier, survey representativeness matters. In total, the ILO study only actually draws on responses from 41 Canadian microworkers. And no more than 13 come from any given platform.

That said, the ILO’s North American average seems likely closer for Canada than Mexico. Socio-economic and other disparities are certainly potentially greater there. But the report also includes only 13 Mexican microworkers, from among the country’s 129m citizens.

Arriving at that $4.70 North American average required the authors make various choices about expressing and prioritizing underlying complexities. And they’re very transparent about this.

Beyond the hours microworkers devote to directly completing tasks, e.g., most spend considerable unpaid time on platforms looking for work. So the $4.70 compensation average very reasonably factors in that extra time.

But when we look at a blended hourly payment figure like this, it’s easy to forget one of crowdwork’s defining features: flexibility. This is particularly extreme in microwork, which leads to huge variation in how and why people do it.

Such short, purely digital tasks can certainly be completed in the eight-hour blocks of a traditional work day. But other workers just occasionally use them fill commercial breaks at home. Some ILO respondents even report microworking exclusively while at other jobs.

Such variation is a major theme of Mary L. Gray and Siddharth Suri’s recent book, Ghost Work.

In traditional jobs, most colleagues have relatively similar hours. Gray and Suri argue that microworkers look more like a “power law” distribution. Essentially, relatively few do most of the work.

Similar patterns repeated across all the platforms studied. On that basis, they divide microworkers into three groups: the “experimentalists, regulars, and always-on.” The key difference is time devoted to microtasking — which usually increases with financial dependence on platform income.

“Always-on” and “experimentalist” microworkers often engaged in quite different work, as we’ll discuss later. But it’s also worth noting that there can certainly still be overlap at the level of particular tasks they undertake. Especially since many of us share a basic intuition that workers handling the same job will tend to resemble one another. Which just adds further opportunity for confusion about microwork.

The ILO report highlights another long-tail distribution, this time in hourly compensation. Accounting for unpaid work, e.g., the median hourly pay across all their respondents is $2.16 USD. But a tiny minority make almost $20 per hour.

In part, this reflects differences between platforms themselves. The researchers found that labour on Microworkers paid a median hourly wage of $1.01, including unpaid time; Prolific, however, pays $3.56.

Such variations often reflect a key factor: where the workers live. National context turns out to be crucial in not only earning patterns but many other aspects of microwork.

Amazon’s policies, e.g., long discouraged workers outside the U.S. or India from using AMT. And platform demographics today still reflect this history.

So on matters from worker compensation to family makeup, the ILO researchers report separately for each country. The decision to effectively present AMT as two separate platforms highlights the importance of distinctively national trends.

The ILO report describes AMT as a clearly “dual-banded” labour market, for instance. Experienced Americans focus on pursuing tasks that pay at or above their federal minimum wage. This leaves lower-paid tasks to inexperienced or foreign workers.

Such aggregate statistics also conceal broad variation, of course. And this is particularly clear in national-level comparisons released since the ILO report.

Lisa Posch and her collaborators, for example, have begun publishing results from a recent survey of almost 12,000 Figure Eight microworkers. And they’ve used the data to compare workers on the platform by country.

This reveals significant differences in motivation. But they’ve also measured international demographic variations. These range from the fact U.S. workers on the platform have incomes higher than the national average to Russia’s seemingly older-than-average micro-workforce.

Then even more significantly, the EU’s Collaborative Economy project has released several pieces of analysis relevant to microwork since 2018.

Based on their extensive COLLEEM survey, these findings draw on data from 32,409 platform workers. This allows direct comparison of the digital gig economies in 14 European countries. Each is essentially represented by as many respondents as the entire ILO microwork survey, whose respondents span 50 countries.

COLLEEM’s added power and comparative approach produce several findings useful as context when considering Canadian microwork.

Maybe most significantly, researchers find clear variation in the amount of microwork the countries’ residents undertake. Levels differ by over 20%. This also isn’t straightforwardly a matter of national income or education levels. Microwork is highest in France and the lowest in Germany, with Slovakia sitting roughly in the middle.

Further study may uncover reliable patterns here. And that could allow reasonable inferences about Canadian microwork levels — or even those of the GTA itself — without direct measurement. But in the meantime, such relatively wide variation reinforces reservations about assuming simple patterns recur internationally.

Finally, it’s worth noting that some key recent developments seem underrepresented or totally absent from the studies discussed above.

AI-related tasks have long helped drive demand for microwork, for instance, and the field continues expanding. But only 8.2% of the ILO study’s respondents worked on such tasks. Then just 7.9% indicated work on content moderation, a field already estimated in 2017 to be employing 150,000 people.

This seems to reflect the ongoing shifts that can make these markets so difficult to track. New microwork is happening, just not on more familiar (and easily studied) open platforms like AMT.

Sources such as Ghost Work emphasize the variety of these alternative arrangements. Early examples here include internal corporate microtask platforms, such as Microsoft’s Universal Human Relevance System or Google’s EWOQ/Raterhub. Companies now often also outsource development or staffing of such services to third-party “vendor management systems.”

This makes microwork still harder to track — even as it’s potentially more present in North America. Long used by companies here to offshore operations, for example, India’s iMerit recently opened its own New Orleans office.

Such developments tie into the emergence of more specialized microwork services. These use tailor-made tools and handpicked crowds to meet the increasing demand for more accurate, confidential work. Florian Schmidt documents exactly this sort of a shift in the auto industry’s increasing engagement of companies such as Mighty AI, Hive.ai and Scale.ai.

There’s also a large and growing ecosystem of microwork platforms/providers operating in languages besides English. Often serving non-western requesters, these largely fall totally outside the literature discussed so far.

China’s massive market offers particularly striking examples. Microwork options there range from task distribution over chat services to emerging “crowdfarms” and specialized data-labelling services.

It seems unlikely Canadians are currently microworking for such services in significant numbers — at least at the national level. But this could change if the global microwork market keeps growing. Such emerging businesses might then provide increasing numbers of Canadians with income. And that’s particularly true of diverse, multilingual cities like Toronto.

Reviewing the sources above obviously still left us with many open questions. It nevertheless helped us more clearly identify key sources of uncertainty. And the process has already pointed us towards promising possibilities for future insights into Canadian microwork.

One key avenue here is the richer data increasingly available about the broader Canadian gig economy.

We originally hoped research on the topic might provide indirect insight into microwork. But there was virtually no scholarly research specifically on gig work in Canada. In fact, a systematic literature review ending in mid-2017 found nothing peer-reviewed on the subject.

The Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives has actually studied the GTA gig economy. But their research focuses exclusively on in-person service delivery. This leaves little to work with for anyone specifically interested in microtasking.

Since then, the topic has thankfully benefited from greater research interest.

In particular, Statistics Canada recently published “Measuring the Gig Economy in Canada Using Administrative Data.” This groundbreaking study is a major contribution to increasingly widespread attempts at quantifying national gig economies.

(The OECD has published a helpful summary, for those curious about work in other countries.)

The research draws on a random sample of linked 2016 tax filing and census data, covering just over 4,780,000 individual citizens. This approach allows remarkably rich detail and accuracy. It also lets researchers explore demographic, compensation and other employment questions particularly relevant for labour force planners.

This new paper remains preliminary. But it charts the broad patterns of independent work in Canada, laying the groundwork for future studies.

Statistics Canada concludes that gig workers made up over 8.2% of all working adults in 2016 — more than 1,674,000 Canadians.

The authors first establish a definition of “gig workers” in the Canadian context. This extends far beyond those making their living with new technologies, to the sort of musicians and actors who coined the term. It also includes all other “unincorporated self-employed freelancers, day labourers, or on-demand platform workers.”

The authors then go on to provide a wide range of fundamental details about this broad gig-worker population, including their income and age distributions. They also sometimes dive deeper, with observations like the fact recent male immigrants work gigs almost twice as often as men born in this country.

The paper doesn’t explicitly address microwork, however. And there’s no clear way to make reliable specific inferences from its broader gig analysis.

Consider the basic question of location. Statistics Canada’s analysis shows that the country’s gig workers are clustered in metro centres such as Montreal, Toronto and Vancouver. So can we safely assume microworkers are similarly concentrated?

Other sources suggest not.

The intuitive parallel doesn’t square, for instance, with work by the JPMorgan Chase Institute (JPMCI). Their team has access to anonymized data from 39 million bank accounts. This allows economic studies without the survey pitfalls already discussed. And they’ve used this very detailed, accurate personal data to produce a range of influential research on the U.S. gig economy.

Like the Statistics Canada paper, for instance, a 2019 JPMCI report found that platform economy participation varied widely between cities. But it also takes a closer historical look at gig work by type, across 27 U.S. urban centres. This shows that transport roles such as driving or delivery overwhelmingly explain differences in cities’ number of gig workers. And as such work increases, they likewise see no evidence people take up other kinds of gigs.

More generally, microwork would fall under the “non-transport platform labour” tracked in JPMCI’s analyses. And they likewise report that earnings for this category are extremely consistent across the 23 states tracked, both big and small.

Gray and Suri’s research provides a further reason for caution about clustering. The American microworkers they studied for Ghost Work are “distributed throughout the United States in both highly and sparsely populated regions.”

This geographic issue is obviously in itself a narrow point. But it hopefully illustrates why even high-quality findings of the broader gig economy might not translate directly to microwork.

The recent Statistics Canada gig paper still offers at least one valuable perspective on microwork. By solidly counting gig workers nationally, it provides added context that can help interpret research such as the BoC’s informal work survey.

This begins with the breakdown in “Measuring the Gig Economy” of how many gig workers are active in each of Canada’s economic sectors. But these proportional numbers alone can’t tell us anything directly about microwork.

That’s primarily because they’re extremely broad. To define work sectors, the authors use categories equivalent to the first two digits of the North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) codes for Canada. Sector 51, for instance, covers “information and cultural industries.” This includes businesses from book and newspaper publishing to film and much of tech.

It’s theoretically possible to identify narrower industries and sub-industries through longer NAICS codes. But even at the 5- and 6- digit levels, there’s nothing yet that specifically captures microwork.

But we might still use such data to estimate an upper limit on Canadian microworkers. Let’s assume that they made up every gig worker in both NAICS sectors (#51 & #54) that include the codes used by major microwork platforms themselves. Then let’s include the entire further sector (#56) covering outsourced administrative and clerical tasks.

Based on the Statistics Canada analysis, these three hired a combined total of just under 549,000 gig workers in 2016. Which therefore seems like a more than reasonable upper limit for Canadian microworkers. Many admittedly might not declare platform earnings, especially if making relatively little. And this could mean they wouldn’t register in the count since the researchers depend partly on CRA filing for their data.

But simply adding sector gig worker totals together also entails significant overcounting, which should offset concerns on that front. Each sector covers many areas, the majority far removed from microwork. NAICS 56, for instance, includes all janitorial services.